plus/minus epsilon

Mercy Housing

11 Aug 2022I’ve been curious for a long time about how nonprofit organizations play a role in the housing market so today I decided to read the published financials of Mercy Housing, one of the largest nonprofit developers in the US.

Mercy’s charitable purpose is to provide housing to families, seniors, and those with special needs who lack the economic resources to access safe housing opportunities themselves. They separate their activities into four arms:

- Capital Partnership. Mercy can provide grant fundraising assistance as well as help raise money from investors for the development of low-income housing projects.

- Housing Development. Mercy both engages in new construction housing development, as well as purchasing and renovating existing properties. When developing for external parties Mercy is compensated by fee, computed as a percent of project cost.

- Property Management. Mercy provides management services to their own buildings, as well as on a contractual basis to owners of residential rental real estate. These services include leasing, accounting, and compliance with regulation. When managing properties for external parties Mercy is compensated by fee, computed as a percent of rental income.

- Resident Services. Depending on the type of housing project, Mercy provides resident services such as senior care, career services, mental health care, so on.

They originally caught my interest because they seemed to have either built or been managing a surprisingly large number of buildings that I just happened to notice, usually because they’re particularly nice. Here’s the list of properties they manage in San Francisco alone (with ones that I already knew about in bold),

| Name | Address | Type | Units | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission Creek Senior | 225 Berry | Senior | 140 | Referral Only |

| Tahanan | 833 Bryant | Supportive | 146 | Referral Only |

| 290 Malosi | Family | 167 | Waitlist Closed | |

| Sister Lillian Murphy Community | 691 China Basin | Family | 152 | Waitlist Closed |

| 455 Fell | Family | 72 | Waitlist Closed | |

| Madonna Residences | 350 Golden Gate | Supportive | 70 | Referral Only |

| Edith Witt | 66 Ninth | Senior | 107 | Waitlist Closed |

| Bill Sorro Community | 1009 Howard | Family | 67 | Waitlist Closed |

| 1100 Ocean | Family | 71 | Waitlist Closed | |

| 1180 Fourth | Family | 150 | Waitlist Closed | |

| 10th & Mission | 1390 Mission | Family | 136 | Waitlist Closed |

| Vera Haile Senior | 129 Golden Gate | Senior | 90 | Waitlist Closed |

| Presentation Senior | 301 Ellis | Senior | 93 | Waitlist Closed |

| Polk Street Senior | 1315 Polk | Senior | 72 | Waitlist Closed |

| Open House | 55 Laguna | Senior | 40 | Waitlist Closed |

| Notre Dame Senior | 347 Dolores | Senior | 66 | Waitlist Closed |

| Monsignor Lyne | 118 Diamond | Senior | 20 | Waitlist Closed |

| Mercy Terrace | 333 Baker | Senior | 158 | Waitlist Closed |

| John King Senior | 500 Raymond | Senior | 91 | Waitlist Closed |

| Francis of Assisi | 145 Guerrero | Senior | 110 | Waitlist Closed |

| Dorothy Day | 54 McAllister | Senior | 100 | Waitlist Closed |

| All Hallows | 1711 Oakdale | Senior | 45 | Waitlist Closed |

| 345 Arguello | Senior | 69 | Waitlist Closed | |

| 1880 Pine | Senior | 113 | Waitlist Closed | |

| 2698 California | Senior | 40 | Waitlist Closed | |

| Westbrook Plaza | 227 Seventh | Family | 49 | Waitlist Closed |

| Natalie Grubb Commons | 255 Freemont | Family | 119 | Waitlist Closed |

| Padre Apts | 251 Jones | Family | 41 | Waitlist Closed |

| Padre Palou | 3400 Sixteenth | Family | 18 | Waitlist Closed |

| Midtown Park Apts | 1415 Scott | Family | 140 | Waitlist Closed |

| JFK Tower | 2451 Sacramento | Family | 91 | Waitlist Closed |

| Heritage Homes | 243 Rey | Family | 148 | Waitlist Closed |

| Columbia Park | 21 Columbia | Family | 50 | Waitlist Closed |

| Carter Terrace | 530 Carter | Family | 101 | Waitlist Closed |

| Britton Court Apts | 1250 Sunnydale | Family | 92 | Waitlist Closed |

| 111 Jones | Family | 108 | Waitlist Closed | |

| 1101 Howard | Family | 34 | Waitlist Closed | |

| 1028 Howard | Family | 30 | Waitlist Closed | |

| Fourth & Channel | 1180 Fourth | Supportive | 7 | Waitlist Closed |

| Mercy Commercial | 1360-1372 Mission | Supportive | 25 | Waitlist Closed |

| The Dudley | 172 Sixth | Supportive | 75 | Referral Only |

| The Rose | 125 Sixth | Supportive | 76 | Referral Only |

| Junipero Serra House | 926 Fillmore | Supportive | 25 | Waitlist Closed |

| Marlton Manor | 240 Jones | Supportive | 151 | Waitlist Closed |

| Derek Silva Community | 20 Franklin | Supportive | 68 | Referral Only |

| Bayview Hill Gardens | 1075 Le Conte | Supportive | 73 | Referral Only |

| Arlington Hotel | 480 Ellis | Supportive | 154 | Referral Only |

| Arc Mercy Community | 1500 Page | Supportive | 17 | Waitlist Closed |

| 205 Jones | Supportive | 50 | Waitlist Closed | |

| Mercy Family Plaza | 333 Baker | Family | 36 | Waitlist Closed |

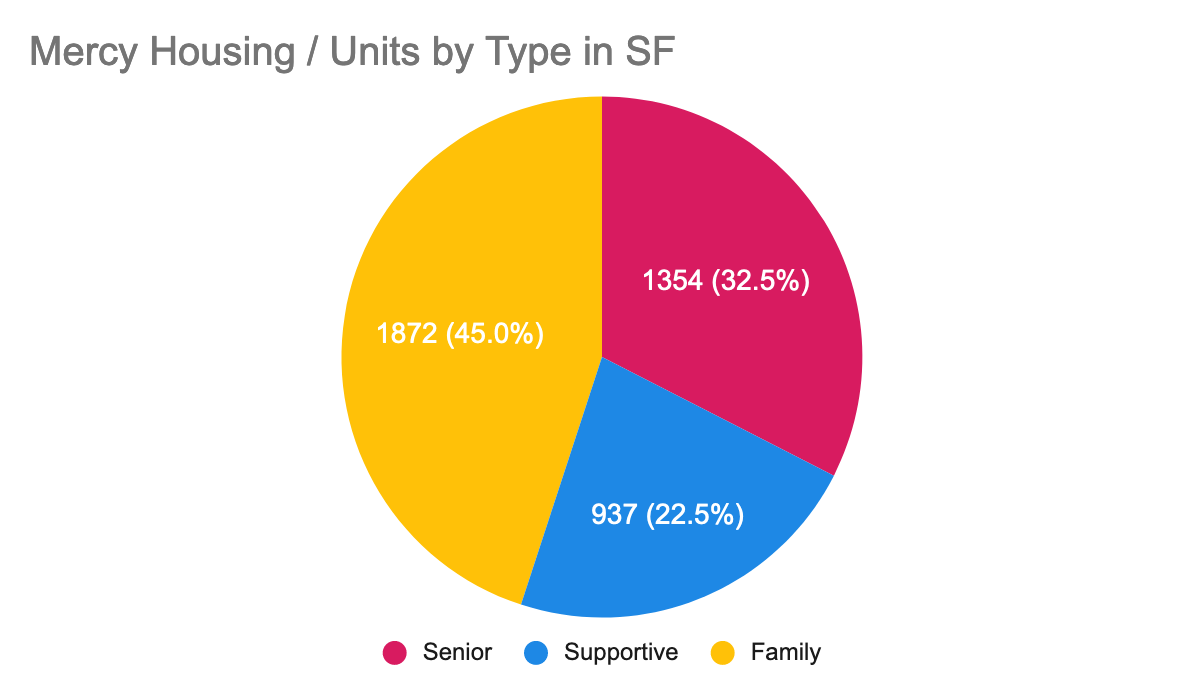

That’s a lot, huh? The total is about 4,100 rental units which means they manage 1% of the entire housing stock in San Francisco. They divide their properties into family, senior, and supportive. Family housing is for working families so it doesn’t provide additional services, senior housing provides assisted living services, and supportive housing provides services targeted toward a specific need like mental illness, physical disability, addiction recovery, or HIV/AIDS care. All three types are considered affordable housing, which means tenants pay 30% of their income in rent+utilities and the rest is subsidized.

The proportion of different housing types, at least in San Francisco, are roughly equal. Mercy states that nationally, 70% of their residents are low-income families, 21% are seniors, and 9% are special needs.

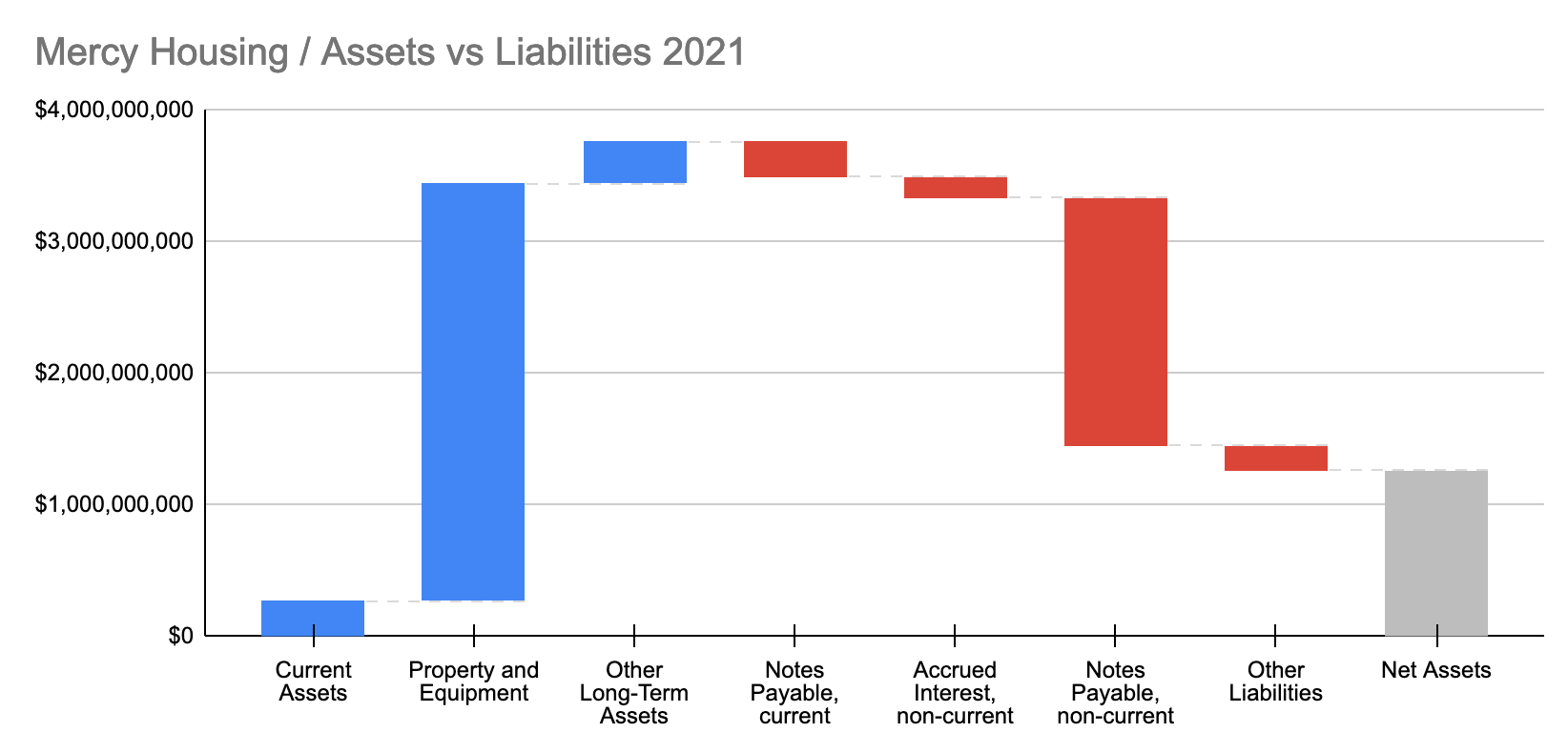

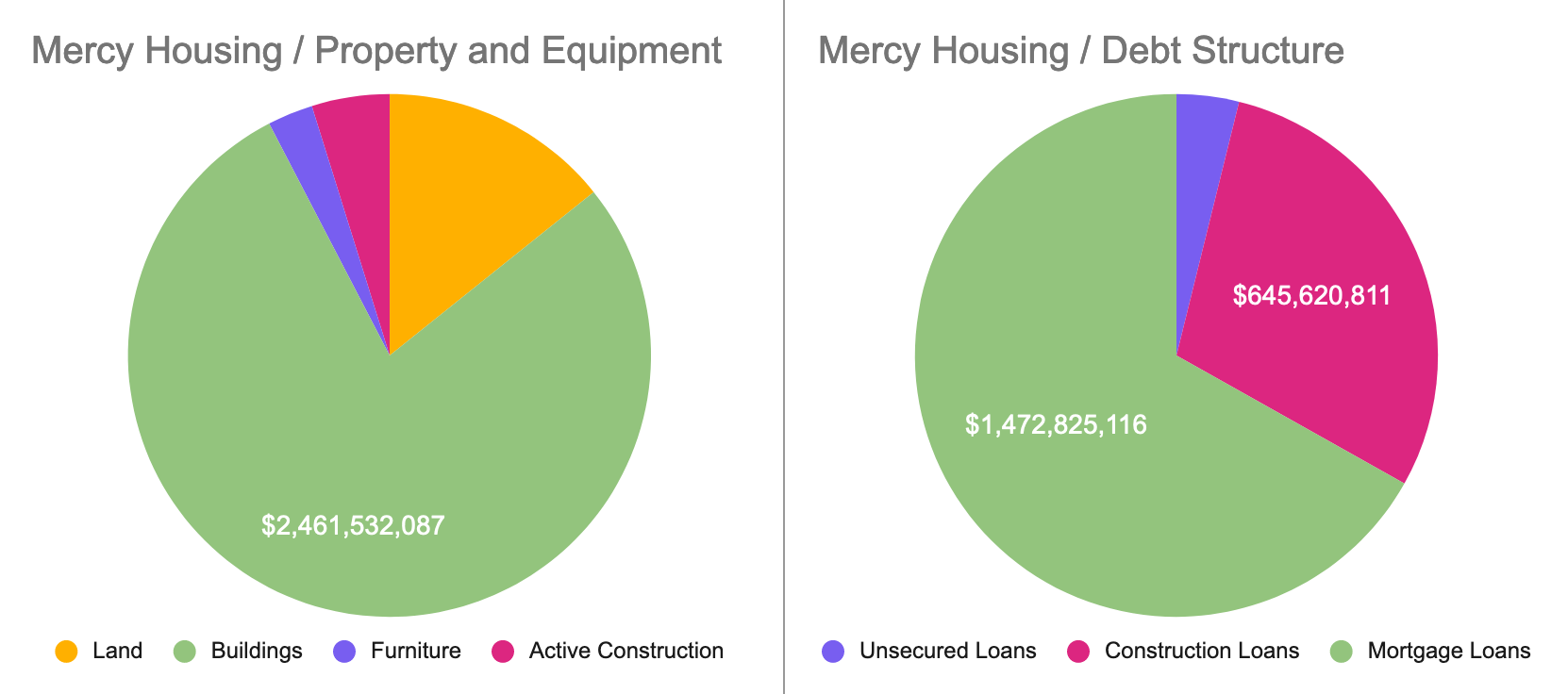

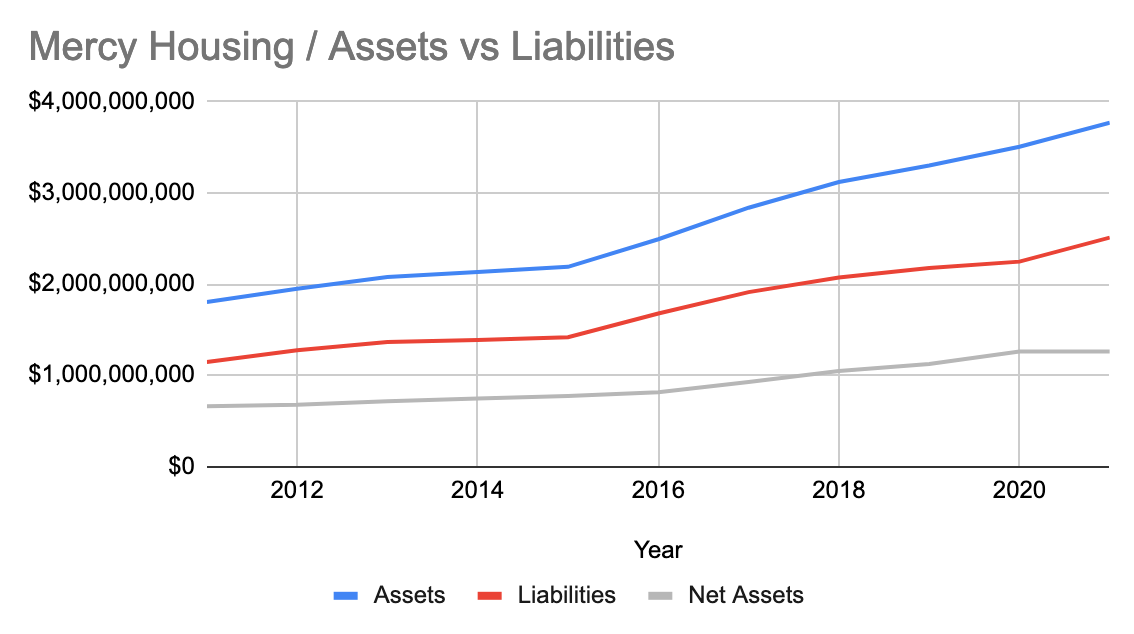

Looking at their balance sheet, they own roughly $3 billion in property with $2 billion in long-term debt, leaving Net Assets of $1 billion. Note that nonprofits have “Net Assets” instead of “Shareholder Equity” because nonprofits don’t have shareholders. Digging down further:

Their assets overwhelmingly consist of buildings and land. A small amount of their debt consists of revolving credit lines from various banks, and a larger chunk of construction loans due in the next 2 years. However, the vast majority is plain mortgage debt maturing over the next 60 years. Mercy also states that they have a small number of swap contracts for the purpose of converting any of their adjustable-rate debt to a fixed-rate.

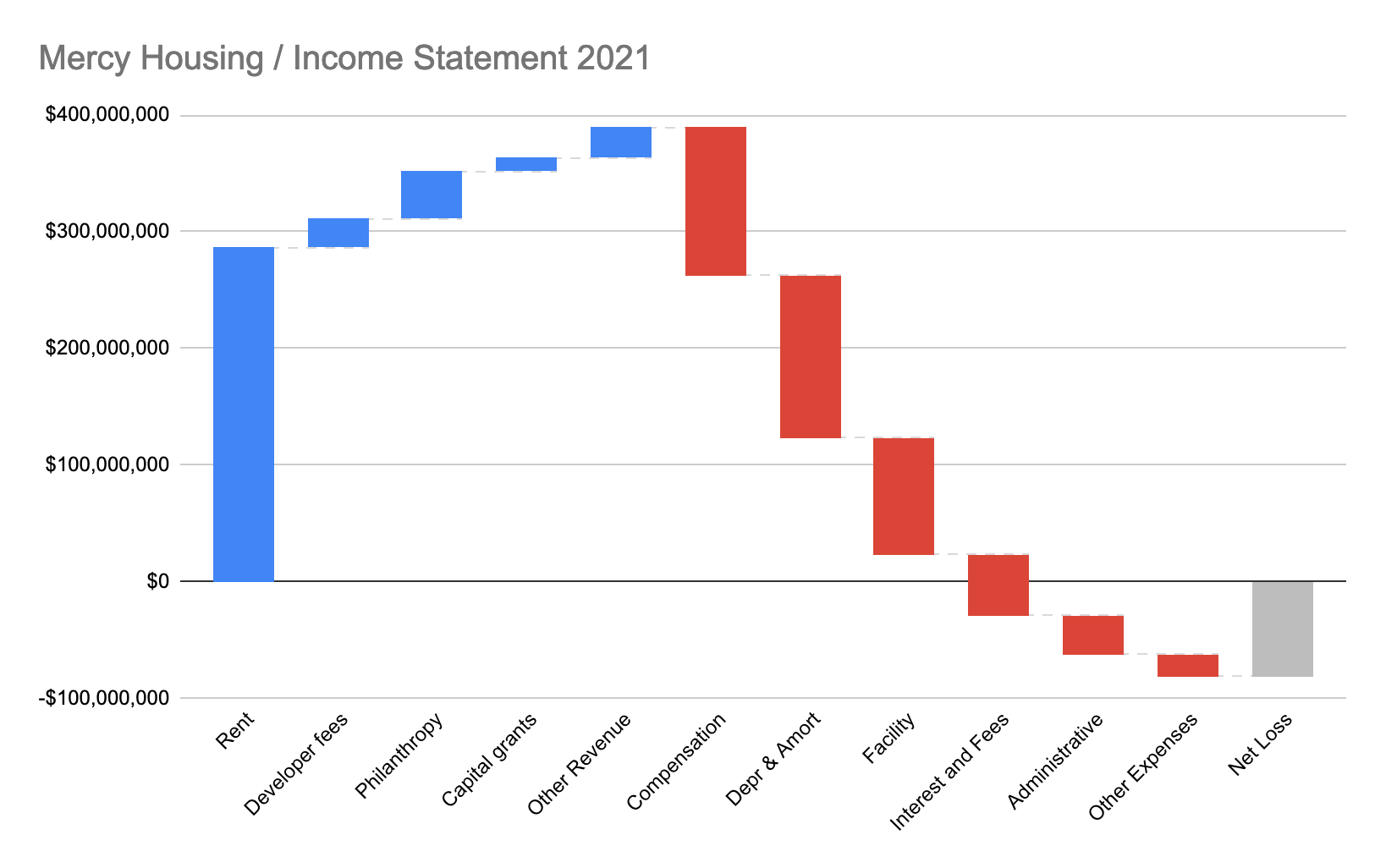

Mercy’s income statement is fairly typical of a real estate company, with the majority of income coming from rent and the expenses largely just consisting of staff, debt, and maintenance. But while it might look like they’re losing money, given that they have a net loss, this is really just a fluke of how subsidiary accounting works when different organizations partner together on projects. While Mercy’s partnerships seem more likely to lose money (and as we'll discover later, this is intentional), Mercy themselves is profitable. Over the past 10 years they’ve grown at an average 7% per year, some years as high as 14%, which seems to be a normal pace in real estate.

They maintain a consistent liabilities-to-assets ratio of 2:3, which means that every $1 of growth in Net Assets is immediately leveraged into $3 of housing. The question then is: what drives their Net Assets growth?

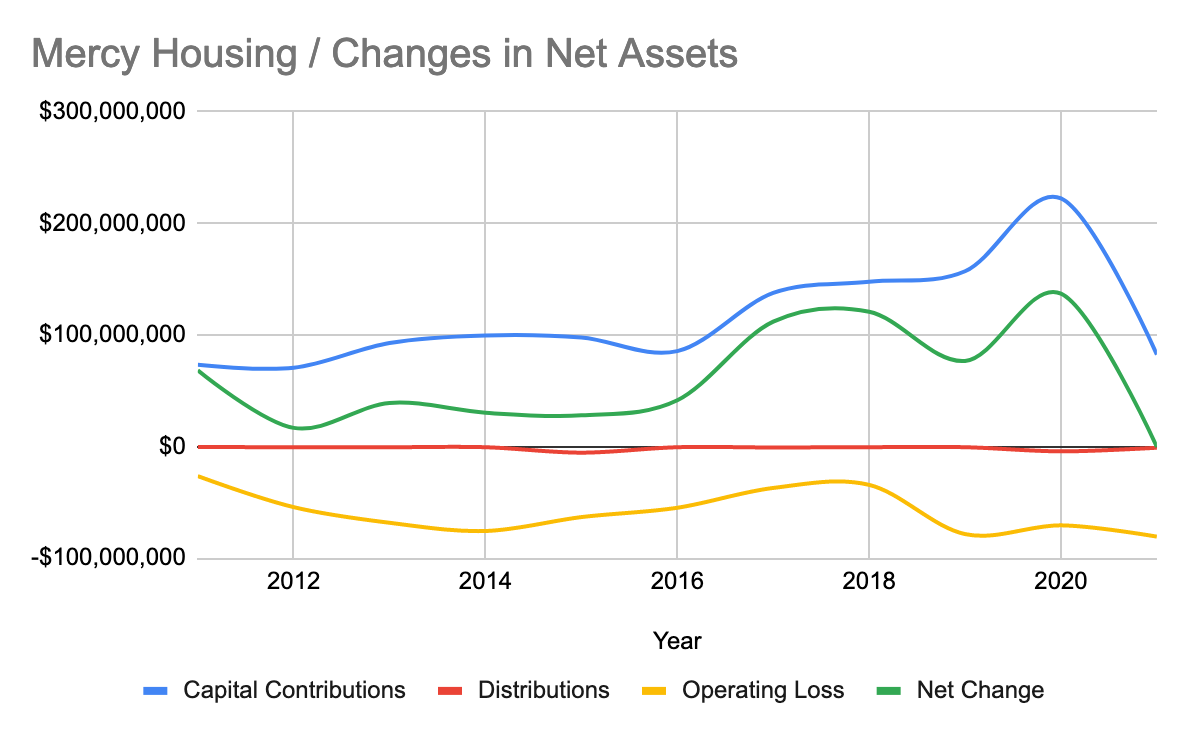

Historically, they’ve raised an average of $115m in equity capital per year, had a consolidated operating loss of $59m, and grown net assets by $60m. Initially this looks pretty weird – nonprofits can’t raise equity? And they’re definitely not supposed to distribute profits. However, a nonprofit can own a for-profit that does those things, and it can back the for-profit with the nonprofit’s resources as long as it has a controlling interest. A controlling interest ensures that the for-profit uses those resources “charitably.” A weird thought.

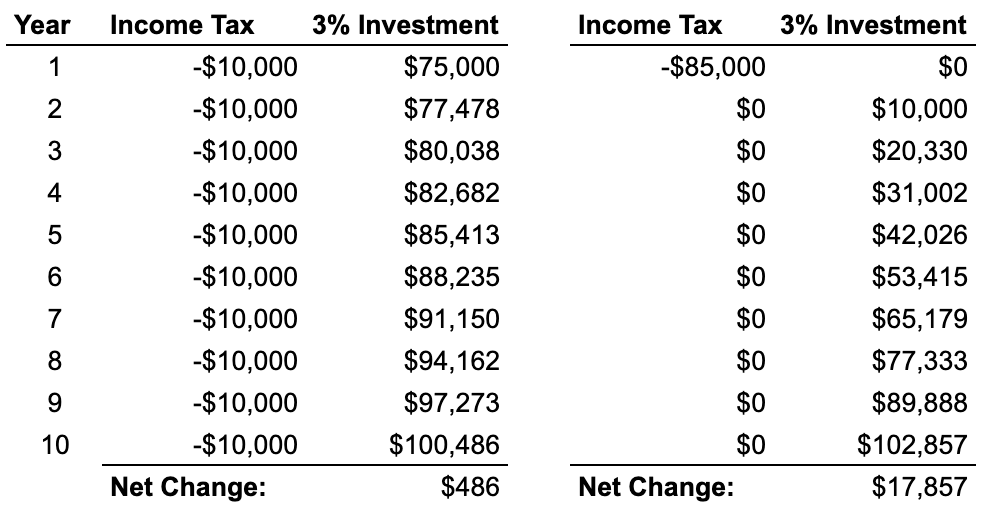

Mercy creates LLC subsidiaries and raises capital by offering Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). This is a program that allows investors who put money towards a low-income housing project to reduce their federal income tax by an amount equal to a fixed percent of the project’s cost each year for 10 years. However private investors don’t have to pay the entire cost of the project to be able to claim the full reduction. Projects are allocated credits by the government with certain properties (what the percent of the project cost can be credited, and usually also a maximum value if the project is over budget), and investors bid up their price in a competitive market. In general a $1 tax credit sells for 85-95 cents, so for example, an investor will put down $85,000-$95,000 in exchange for a $10,000/yr reduction in federal income tax each year for the next 10 years ($100,000 total).

That’s similar to an investment with a 1-4% internalized rate of return. I decided to model it by looking at one scenario where we simply pay our $10,000 income tax bill every year and put $75k into a compounding 3% investment, and another scenario where we negate our tax bill in year one with an LIHTC and invest the saved money from the 9 following years into a 3% compounding investment.

This ends up being a pretty good decision. Particularly if your investments are already in the 1-4% return range, then the slight reduction in tax rate frees up more capital for investment later which compounds the benefit further. Partnering with Mercy very likely has further benefits that are harder to determine from the outside – for example, capital partners can claim the operating loss of a property which would further reduce taxable income, despite not actually contributing to the operation of the property.

Conclusion

This largely gets to the end of my understanding of Mercy Housing’s operations:

- They raise capital by offering tax credits to private investors

- They leverage that capital into construction and mortgage loans

- Raised capital and loan proceeds are put into low-income housing projects

- Government-subsidized rental income largely pays for the long-term debt, maintenance, and services at those properties.

Admittedly it’s disappointing that tax revenue is the primary source of funding. Government regulation is the main restriction on market-rate housing in the first place, and then the government is paying the inflated development and rental costs that it itself caused to house those that were priced out.

There also seems to be a significant coordination problem, since local governments are the most active in regulating the supply of housing, through zoning, planning, and rent control. However, the federal government is the most active in subsidizing housing, and the federal government has an extremely limited ability to influence the decisions of local governments.